Title: “Who is this?”

Date: April 17, 2011; Palm Sunday

Texts: Ps 118, Matt 21:1-11

Author: Isaac Villegas

Jesus is the talk of the town. Crowds gather along the streets. Some are there to welcome God’s prophet, the one who will speak God’s truth about the world. Others are there to welcome a messiah, the man of God who will restore justice in the land, who will right the wrongs, who will topple corrupt leaders, who will set the people free from their oppressors. And many are there because they hear rejoicing in the streets; they want to see what the fuss is all about.

Matthew 21, verse 10: “When he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in turmoil, asking, ‘Who is this?’” In the middle of all the shouting, there were people new to the parade who were trying to figure out why everyone was so excited: Who is this guy? Why is he on a donkey? What’s the big deal?

Jesus gives the crowd a clue about who he is. He rides into Jerusalem, not on a powerful horse, fit for a king, but on a lowly donkey. He doesn’t come in on a horse ready for war, ready for triumph. Instead, Jesus sits on a donkey, an animal fit for humble work, for hauling food and supplies. A king who shows up to his welcoming party on a donkey is saying something about his reign, something about his kingdom. As we follow this story, we soon find out that this strange king doesn’t take the throne of worldly power; instead he is humiliated on a cross, naked and weak. On a donkey, Jesus rides his way to the cross.

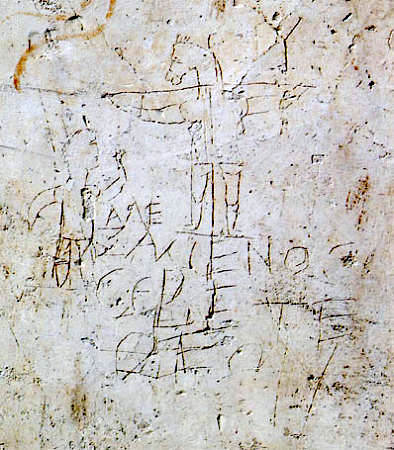

A while ago archeologists in Rome found some ancient graffiti, a picture, possibly from the 1st century. The graffiti is a picture of a cross, and on the cross there’s a donkey, a crucified donkey. Beside the crucified donkey is stick-figure man looking up at the cross, holding up his hand, which is probably a gesture of worship. Below the image are couple words, an inscription: it says, “Alexamenos worships his God.” This graffiti has been interpreted as an insult directed at the early Christians. The Christian God is a dumb ass, who died on a Roman cross, a failed king, executed by the strong, mocked in the courts of imperial power.

There’s another inscription near this graffiti; the words appear to be in a different hand. It says, “Alexamenos is faithful.” It’s a response to the insulting image. It’s like those graffiti wars we see on the sides of buildings and down alleys: one group tags a wall with spray paint, and another group responds with their own graffiti. Instead of being embarrassed by the insult, this ancient Christian graffiti artist owns it: Yes, our king rides a humble donkey, not a mighty warhorse. And, yes, the way of our King leads to the rejection of the cross, not the glorious thrones of earthly power.

After Palm Sunday, after Holy Week, after Easter, during the first centuries of the church, some people will answer the question about Jesus’ identity—the “who is this?” question—they will answer the question with an insult to him and his followers: Your God is a crucified donkey, powerless against the forces of this world, weak in comparison to the kings of war.

But for now, on Palm Sunday we are invited into the crowds of people in Jerusalem who follow this king who rides on a donkey, whose kingdom will be ridiculed as weak and insignificant. Some of us find ourselves among the people in the crowd who are ready to welcome Jesus, to shout his praises from the street corners, to say with the Psalmist, “You are my God, and I will give thanks to you,” for I have seen your light in the world (Ps 118:26).

Others of us might not be so confident about God’s power in the world. No matter how much we squint and stare, we have a hard time seeing the light of God’s hope shining through the darkness in our world. Yes, we are also in the Palm Sunday crowd, but we may not be on the front lines, waving palm branches, and shouting verses from the Psalms in the middle of the city. Instead, we might be peeking from behind the people in front of us, watching Jesus, and asking, “Who is this?” We find ourselves in the crowd because Jesus is a live question for us. We can’t help but keep on wondering about him, about who he was, about who he is, about when he might show up again.

A few months after I started coming to church here (almost eight years ago), someone said something during our sharing time that has stuck with me. She said something like: I don’t know if I’m still a Christian anymore, but whatever I’m becoming, I can’t help but come back here and wrestle with the questions that won’t go away.

She kept coming back to church because, as much as her faith seemed to be fading away, she couldn’t help but keep on wondering about Jesus—not just the Jesus we find in our bible stories, but the Jesus who makes a difference in our lives. She stayed with us, always asking, always wondering, “Who is this?”

Through her questions, she showed me that part of the mission of the church is to keep alive the question of Jesus in our world. The church lives by the persistent questioning Jesus poses to our lives and to the world.

We are, in a sense, haunted by Jesus—always coming back to him, always wondering about his presence, where we might find him, always thinking about what difference he might make in our relationships and in our work and in our politics.

I am reminded of the words of an eccentric British theologian, Donald MacKinnon. He said, “If I ask myself why I remain in some sense a Christian, it is because of the questions set to me by the person of Christ.”[1] MacKinnon, it seems, also found himself in the crowds on Palm Sunday, wondering aloud, “Who is this?”

But, if we really want an answer to our questions about Jesus, if we really want to know who he is, we have to follow him, we have to stay with the crowd that follows him. Palm Sunday is a procession to the cross—that’s where our praises and questions lead us to Golgotha. As the 16th century Anabaptist-Mennonite, Hans Denck, wrote: “We cannot know Christ unless we follow him daily in life.” We cannot know Christ unless we follow him daily in life. For us, knowing is a way of life. With Jesus, to know him has as much to do with our hands and feet as with our thoughts.

On Palm Sunday, you are in the crowd. You are here, part of this group, assembled around Jesus. Maybe you are here to offer your praises, full of certainty and hope. Or maybe you are here to keep your questions alive, to keep on wondering, to wrestle, to struggle, to ask again and again, “Who is this Jesus?”

Either way, you are here and that’s what matters, at least for now. You are in the crowd, gathered around Jesus. But Palm Sunday leads into Holy Week, where we remember the passion of Christ, his rejection by the world, his abandonment by his friends, and his humiliation on the cross. This one who rides into town on the donkey will make his way to Golgotha, the place of crucifixion.

But for now, on Palm Sunday, you are where you need to be: in the crowd. But soon, as we enter our week, Jesus will ask his disciples a question, he will ask us a question: Will you stay with me, will you share in my rejection, in my shame, in my humiliation?

If you know how the story goes during Holy Week, you will remember that the disciples of Jesus don’t stay with him in his darkness hour. They scatter in fear. They try to make themselves anonymous, to disappear into the crowds who watch the spectacle of crucifixion from a safe distance.

The friends of Jesus probably end up wondering to themselves, as they watch their king, the prophet who comes in the name of the Lord, the messiah—as they watch him die, they can’t help but wonder with the crowds: “Who is this?”

The good news of Easter is that Jesus comes back. He comes back from the dead—that’s what grace is all about: that Jesus always comes back, even when we abandon him in his most needy moment. Jesus comes back and keeps the question of faith alive, this question that we can only answer with our whole lives.

Who is this man Jesus? The answer comes to us as we follow him.

So, come, let us follow him to the cross, that we may know him, that we may draw near to him; because he has come back from the dead to draw close to us, again and again, to say to us, to say to you: Here I am, I will never leave your nor forsake you, even though you have forsaken me.

[1] Donald MacKinnon, Borderlands of Theology (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1968), p. 26.